When Cyclone Montha slams into the Andhra Pradesh coast near Kakinada on the evening of October 28, 2025, it won’t just be another storm—it’ll be the most powerful system to threaten the region in nearly five years. With sustained winds of 90–100 km/h and gusts hitting 110 km/h, the India Meteorological Department (IMD) has issued a red alert for seven coastal districts, while Andhra Pradesh State Disaster Management Authority (APSDMA) has evacuated over 120,000 people. The storm, currently 560 km off Visakhapatnam, is moving northwest at 18 km/h, and its arrival won’t just mean wind—it’ll mean water, power cuts, and a race against time to protect lives.

Storm Gathers Force Over the Bay of Bengal

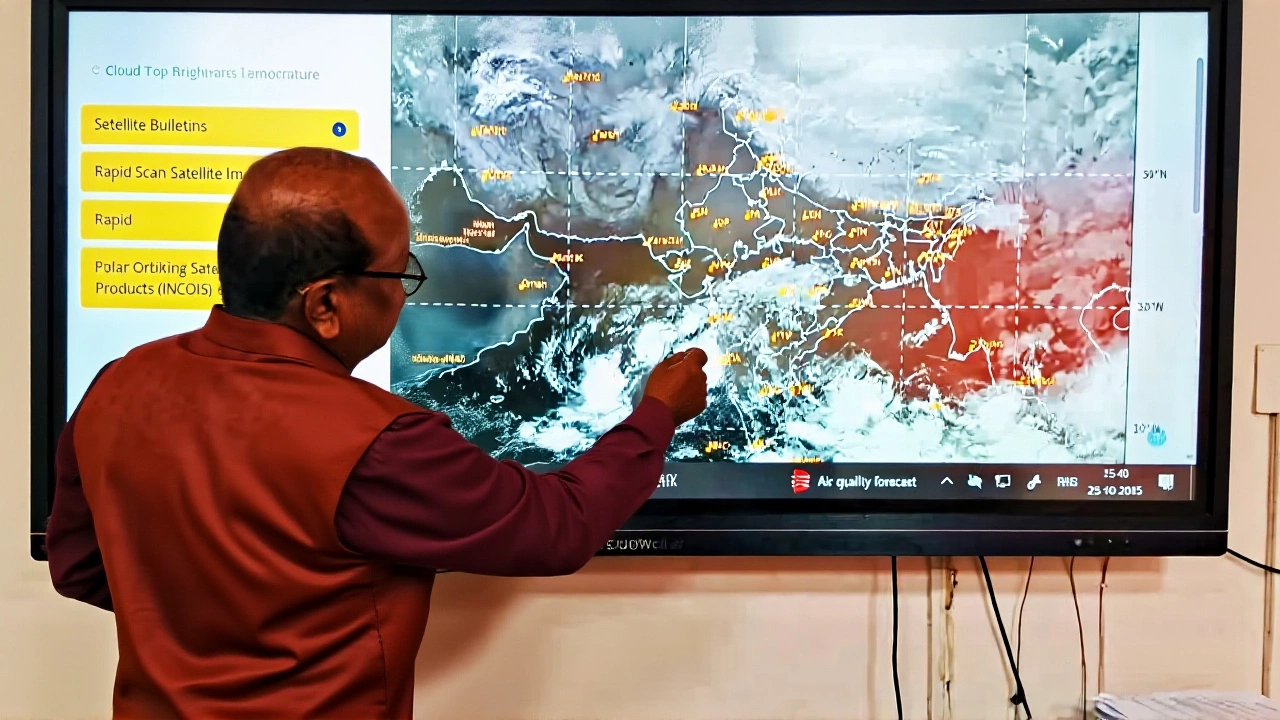

As of October 27, 2025, at 2:48 AM UTC, Cyclone Montha was centered at 13.3°N, 84.0°E—1,067 km south-southwest of Kolkata and 450 km southeast of Kakinada. Winds had already climbed to 85 km/h, with waves reaching 5.5 meters off the coast. The Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) confirmed the system would intensify into a severe cyclonic storm before landfall, despite increasing wind shear and dry air intrusion. That’s unusual. Most storms weaken under those conditions. But Montha’s core is stubbornly compact, drawing energy from unusually warm sea surface temperatures—29.5°C, nearly 2°C above average for this time of year."Cyclone has begun," said Prakhar Jain, Managing Director of APSDMA, at 5:13 PM IST on October 27. "Coastal districts are witnessing rainfall accompanied by gales." His team has been tracking the storm’s speed shift—from 19 km/h to 18 km/h in the last six hours. That slight slowdown means more time for rain to dump over the same areas. And that’s dangerous.

Red Alerts, Evacuations, and the Race to Prepare

The IMD’s red alert covers Kakinada, Konaseema, West Godavari, Krishna, Bapatla, Prakasam, and SPSR Nellore—districts where homes are often built on low-lying land, and drainage systems are overwhelmed even by moderate rain. Orange alerts stretch into southern Odisha and northern Tamil Nadu, where schools have been shuttered and hospitals placed on emergency standby.More than 120,000 people have been moved to 842 relief shelters, according to APSDMA. Many are in schools and community halls, some with just basic cots and bottled water. The state’s N Manohar, Civil Supplies Minister, confirmed a meticulously planned logistics operation: "We’ve positioned 38,000 metric tons of rice, 12,000 tons of pulses, and 5 million liters of diesel at strategic depots. Fuel is as critical as food." The Public Distribution System (PDS) is being activated before the storm hits, not after. That’s a lesson learned from Cyclone Phailin in 2013, when supply chains collapsed.

Maritime Chaos and Air Disruptions

The Indian National Centre for Ocean Information Services (INCOIS) warned of 2–4.7 meter waves along the coast from Nellore to Srikakulam. Fishermen, who make up nearly 15% of the population in these districts, have been ordered not to go out to sea from October 25 to 29. Over 7,000 boats have been secured in harbors. Some ignored the warning. Six bodies were recovered off the coast of Visakhapatnam on October 26—reminders of how quickly the Bay of Bengal turns deadly.Six flights between Chennai and Visakhapatnam were canceled. Rail services on the Vijayawada–Kakinada line are suspended. Road access to Kakinada is being restricted to emergency vehicles only. The European Commission’s ECHO noted that the storm’s projected path—between Amalapuram and Narasapur—aligns with areas where infrastructure is weakest. Many bridges were built decades ago, with no modern storm surge standards.

What Comes After the Wind

Landfall isn’t the end. It’s the beginning of the real crisis. The JTWC predicts Cyclone Montha will weaken steadily after hitting land, dissipating in roughly 36 hours. But heavy rainfall? That’s expected to last three full days. Forecasters say some areas could receive 250–350 mm of rain—enough to trigger flash floods and landslides in the Eastern Ghats foothills.Power lines are already down in parts of Prakasam. Mobile towers are being pre-shutdown to prevent electrocution risks. The state’s emergency response teams have been trained for post-cyclone scenarios: disease outbreaks, water contamination, and disrupted supply chains. Last year, after Cyclone Biparjoy, cholera cases spiked in Sindh. Officials here won’t repeat that mistake.

Why This Storm Matters

Cyclone Montha isn’t just a weather event. It’s a stress test for India’s disaster infrastructure. The country has invested billions in early warning systems since 2013. But preparation doesn’t always equal protection. Many homes in Kakinada are still made of tin and mud. The elderly, children, and disabled remain vulnerable—even with shelters. And while the government’s response has been swift, the real question is: How many people are still waiting for help?Climate scientists point out that Bay of Bengal cyclones are intensifying faster and staying stronger longer. The last time a storm of this magnitude hit near Kakinada was Cyclone Gaja in 2018. Back then, 48 people died. This time, with better warnings and evacuations, officials hope the death toll stays under ten. But nature doesn’t follow plans. It follows physics.

Frequently Asked Questions

How many people are affected by Cyclone Montha?

Over 120,000 people have been evacuated from coastal districts of Andhra Pradesh, with an additional 300,000 in Odisha and Tamil Nadu under orange alerts. Nearly 2 million residents live in the storm’s projected path, and over 7,000 fishing vessels have been grounded. The most vulnerable are those in informal settlements near rivers and coastlines, where evacuation access remains limited.

Why is Cyclone Montha stronger than expected despite wind shear?

Despite wind shear above 55 km/h and dry air intrusion, Montha’s compact core and unusually warm sea surface temperatures—29.5°C, 2°C above average—are fueling its resilience. Most storms weaken under these conditions, but Montha’s rapid intensification phase before landfall, combined with low vertical wind shear in its inner core, allowed it to maintain strength. This pattern matches recent trends in the Bay of Bengal, where warming waters are overriding traditional weakening factors.

What’s being done to prevent post-storm disease outbreaks?

The Andhra Pradesh health department has pre-positioned 1.2 million water purification tablets, 50,000 doses of oral rehydration salts, and 300,000 doses of antibiotics in relief centers. Teams are ready to deploy rapid-response units to test water sources within 24 hours of landfall. Cholera and dengue are top concerns, especially in overcrowded shelters. Mobile clinics are being staged in 15 districts to monitor for symptoms immediately after the storm passes.

How does this compare to past cyclones in the region?

Cyclone Montha is comparable in intensity to Cyclone Gaja (2018), which had 110 km/h gusts and killed 48 people. But unlike Gaja, which made landfall at night, Montha is expected to hit after dusk on October 28, complicating rescue efforts. It’s also stronger than Cyclone Hudhud (2014), which struck Visakhapatnam with 185 km/h winds but affected fewer people due to lower population density. Montha’s proximity to Kakinada—a major port and industrial hub—raises economic stakes far beyond previous storms.

Will power and internet be restored quickly after the storm?

The state has deployed 120 mobile transformer units and 800 repair crews on standby, but restoration could take 5–7 days in the hardest-hit areas. Fiber-optic cables along the coast are vulnerable to flooding, and mobile towers may remain offline for up to 72 hours. Emergency satellite phones have been distributed to 500 relief centers. The government is prioritizing hospitals and water treatment plants for first-phase restoration.

What’s the long-term outlook for cyclones in the Bay of Bengal?

Studies from the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology show Bay of Bengal cyclones are becoming more frequent and intense, with a 30% increase in severe storms since 2000. Warmer waters, rising sea levels, and changing wind patterns are contributing factors. Without major coastal infrastructure upgrades and mangrove restoration, areas like Kakinada and Srikakulam could face annual threats by 2040. Montha is a warning—not an anomaly.